MANGO TOWN, Liberia | Golden and draped in red, white, and blue ribbons, the spelling trophy won by Mango Town School has become more than a source of orthographic achievement for the students and their teachers. It has brought a wealth of attention to a school that was largely forgotten.

Before clinching the spelling contest sponsored by the Liberian government, the primary school was deemed “not conducive” to learning, according to Principal Joseph Dweh, and had too few textbooks, desks, and classrooms for its 307 children.

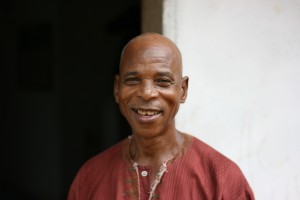

Mango Town Principal Joseph Dweh says a spelling bee helped his school gain recognition. Photo by Timothy Spence

“I mean, we were completely neglected by the government,” Dweh said from his small office in the mud-walled school. “The children’s right to education was infringed upon until we won the spelling bee.”

Mango Town School has been around since the 1950s but was abandoned through much of Liberia’s 14-year civil war. The school reopened in 2005 and has had little attention since.

The Ministry of Education has now vowed to build a new school this year and give more attention to Mango Town’s needs, Dweh said. The nine teachers, who had not received their pay for months, also got promises that their salaries would be paid more regularly.

“Had it not been for the spelling bee that we won, then we would not have had any attention here,” said Varfley Kenneh, a teacher.

Fatu Kamara, 13, a third-grader who participated in last September’s spelling contest, also said the trophy has brought changes. “I feel happy that we were able to win the spelling bee competition, because it made us start getting textbooks, copybooks, and other things that our friends can receive at their schools.”

Daunting Challenges

The trophy notwithstanding, Mango Town is a microcosm of a national education system facing daunting challenges. Liberia has Africa’s lowest primary school enrolment rate – 30 percent – despite primarily school attendance being compulsory since 2006. The net school enrolment rate is 5 percent, according to the government’s 2010 Education Sector Plan, and 36 of the nation’s 92 districts have no high schools. Net enrolment is based on the number pupils attending classes appropriate to their age.

Girls are more likely than boys to repeat a class, to drop out of school, and to be illiterate, despite concerted efforts to help them and keep them in the classroom. According to recent government health and population surveys, 56 percent of Liberian women never attended school and it is not unusual for high school classes to be overwhelmingly male.

The male-female disparity extends to teaching staffs. Only 3 percent of the nation’s high school teachers are women, according to the Education Ministry. Public schools, especially those outside the capital, Monrovia, face a dire shortage of qualified teachers. Most rural schools depend on “volunteers” or “recruits” who have little formal education themselves. Although these teachers are entitled to pay, they are not certified and do not get full civil-service benefits. That means salaries are erratic.

School administrators complain that there is often a disconnect between what the government and international aid groups do, and what schools really need. Teachers and administrators say the national education hierarchy ignores local input when it comes to planning and building facilities.

“Schools are being dedicated in remote areas where there are no students, and there are too many overcrowded schools that have to go begging,” said one international aid worker involved in education training and planning. “You can’t blame the government entirely because they are trying, but there is just too much of one hand not knowing what the other is doing.”

A Mango Town student holds the trophy the school won in a government-sponsored spelling bee. Photo by Timothy Spence

Liberia has faced a monumental task since the civil war ended in 2003, and not just in rebuilding its educational system. During the fighting that began in 1990, infrastructure was ransacked, state services were disrupted, and rival warlords looted or destroyed public property. More than half the public schools were ruined, according to Education Ministry.

The fighting left some 200,000 people dead, while an estimated 750,000 Liberians, of a population of 3.5 million, fled to other West African nations. Many have returned, overwhelming a nation that is trying to rebuild schools, infrastructure, and other state institutions.

Backed by generous international support, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has made education a priority since taking office in 2006. The Ministry of Education gets the largest allocation from the country’s budget – US$43 million this year, or 12.4 percent of public spending. International donors and aid agencies also provide substantial assistance and contributions through school construction and training.

The European Union plans to spend 125 million euros (US$165 million) on Liberian education and health through 2013, while the U.S. Agency for International Development alone provided US$33.5 million for educational programming in 2010. Plus, 14 American Peace Corps volunteers will take up teaching posts this year, returning to the country for the first time since 1990.

When Payday Doesn’t Come

Still, school administrators complain of not receiving promised operating funds and non-civil service teachers often say they are not paid for months at a time. Mango Town’s Dweh believes that free and compulsory primary education can be realised only if students are encouraged with textbooks, book bags, uniforms, notebooks, and other supplies.

He also said teachers without certificates, currently the backbone of the nation’s teacher corps, deserve regular pay. Teachers earn a minimum US$80 monthly.

At Bopolu Central High School in Gbarpolu County in northwestern Liberia, 18 of the 34 staff members are not certified teachers. “Most of the recruited teachers are in the senior high school, so when the teachers are not paid, it affects [the seniors] the most,” said John V. Lombeh, the vice principal for instruction.

Teachers at Bopolu Central High School in Gbarpolu County say their input is often ignored by Liberia’s education bureaucracy. Photo by Timothy Spence

Teachers are getting frustrated, he said, and looking for other work, even in a country where eight in 10 people have little or no work. Bopolu’s only high school chemistry teacher left to work for a mining company after going for months without pay. Some teachers fight back – they have launched peaceful demonstrations in Monrovia, and administrators at Bopolu say the instructors sometimes hold back their grades or refuse to go to class to draw attention to their plight. As salaries were being handed out three days before Liberian Independence Day on 26 July, some of the non-civil-service teachers said they had not been paid in five months.

Bopolu, located in a lush countryside of rolling hills four hours’ drive north of Monrovia, is accessible only by roads that become rivers of mud during the rainy season. A new classroom block was built this summer so that primary school students could attend class separate from the senior high school located up the hill. But Lombeh worries about having enough teachers as the new academic year starts and says it is nearly impossible to recruit teachers from Monrovia, home of the state university, due to insufficient housing and other inducements.

He also worries about poor sanitary conditions and no water. “It’s our biggest challenge,” Lombeh said outside his office as sun broke through the dense clouds after a downpour. “There is no water for sanitation for the girls and the cooks have to walk into the village to get water for cooking. We have a water tank but it has a crack and doesn’t hold water. We have asked for help, but we still have no water.”

Mohammed Kamara, a Bopolu teacher whose children attend the local public school, also worries about how schools are run.

“As a parent you want the children to have quality education,” Kamara said. “We don’t have that here.”

In Mango Town, just off a paved road that leads to Monrovia, school conditions overshadow other problems. There are no toilets, not enough desks, no electricity, and only enough books for every fourth child. “The class is not spacious enough to move around in, the children get dirty fast because of the dirt floor, and the condition of a school also has an effect [on learning],” kindergarten teacher Esther Gweamee said.

Gweamee said she finds it difficult to prepare her lessons in the absence of a curriculum or teaching materials, an acute problem in a country that until last year had only one textbook for every 27 students. “We strain ourselves to find topics to reach to the level of these kids,” she said.

Mango Town’s principal, Dweh, said his school has not received some government subsidies for two years, meaning he turns to parents and community members for chalk and other materials. When Mango Town School reopened five years ago, the school was so small some classes were held in a village mosque for lack of classroom space. More recently, overflow classes are held in an unfinished house across the street.

Not Doing Their Homework

Some educators say that although the government is trying to improve schools, there are inconsistent and often contradictory policies. Rules are issued and rescinded, and decisions about supplies or construction are made without consulting local districts – problems administrators did not deny in interviews for this article. Principals were told not to hold classes with more than 45 students per teacher, forcing schools to hold two or three shifts a day to accommodate all the students. Teachers who are not qualified in subjects are asked to handle overflow classes.

President Sirleaf in April named a new education minister and deputy minister for instruction after suspending the previous officials in part for the poor conditions at some schools. Since then, the Ministry of Education announced that beginning this academic year, dilapidated schools, including Mango Town, would not be allowed to operate. But there were no apparently plans to provide temporary classrooms.

“If the government is really serious about that, then I am afraid that they will be denying thousands of children access to education around the country,” said Konah Burphy, a teacher in Royesville, Bomi County, west of the capital. “I think what they can do is try to improve the facilities of those schools.

A pile of desks at Mango Town School before the new class year begins. Some students have to bring chairs from home because of shortages. Photo by Timothy Spence

“Some schools do not even have benches for the children to sit on, so they have to carry along with them their seats, they have nowhere to relieve themselves apart from bushes, no safe drinking water at these schools,” Burphy said. “These are things that the government needs to start to address instead of saying these schools would not be allowed to operate this school year.”

Despite repeated attempts to arrange an interview, Education Minister Othello Gongar could not be reached for comment on educational conditions and policies.

Overcrowding has grown as the government has pushed to expand education as well as retain those in upper grades. School enrolment doubled after the war ended, from 260,499 in 2005 to 539,887 two years later, and continues to grow.

Compounding the overcrowding is a disproportionate number of older students, some over age 20, who missed out on education during the war years or were recruited as marauding fighters and now are going to school. The government has extended its Accelerated Learning Program, designed to compress six years of primary education into three, to accommodate students older than 15. More than 68,000 ALP students were enrolled in 2009 compared with 38,990 in 2005, according to the government’s 2010 Education Sector Plan.

Eric Gbah, 19, a senior at the Gray D. Allison High School in Monrovia, said he goes to school as early as 6 a.m. to ensure he gets a seat in the front row of the class. “We were more than 100 last year in the 11th grade. If you are not on campus by that time to secure a seat, then you will have to stand until the end of the school day.”

Despite overcrowded conditions in the capital, Montserrado County Superintendent Grace Kpan has announced that she wants all children removed from the streets of greater Monrovia and sent to school when classes start on 1 September. She has already begun running radio programs in the capital region and planned to circulate leaflets to educate parents on the dangers of children in the street, and to instruct families that children should either be in school or at home.

It’s Spelled M-A-N-G-O T-O-W-N

At Mango Town School, the principal, teachers, and students are hoping the coming school year will mean a new building, better resources, and regular pay for teachers.

And they are convinced that the spelling trophy, with its ribbons in the national colors, has brought good luck since the students won it on 25 September 2009, defeating a team from a nearby junior high school.

Mango Town School is located in a community of 15,000 in the greater Monrovia region. Opportunity knocked one day when Sirleaf was visiting a nearby privately financed school for children with disabilities – a building shiny with fresh paint, with a water supply, ample desks, and toilets – facilities the public school doesn’t have.

Mango Town’s chief has provided support for the village school, allowing students to use a local mosque as a classroom when the school first re-opened in 2005. Photo by Timothy Spence

According to Dweh, the president’s motorcade passed Mango Town School. Dressed in their uniforms, the students went out to greet the president with their spelling trophy and caught her attention. She stopped to greet the students, and that, says Dweh, was the tipping point. After that, the school suddenly got recognition from the Ministry of Education and the district schools chief, and won promises of a new building and a resolution to some of the resource problems.

But efforts to build a new school were held up by a land claim on the school’s property, and during the summer break, the school’s principal – like those in other rural Liberian primary schools – still had not received some operating funds that were already two years in arrears.

Dweh is confident that Liberia’s educational outlook is positive and that more help for his school is coming. But asked how he operates with unpredictable funding, grim conditions, and teachers who sometimes go unpaid, he smiled and said, “By God’s grace. By God’s grace.”

This article was written as part of an education training program for journalists run by Transitions Online in Prague and sponsored by the Open Society Institute with the contribution of the Education Support Program

Tags: Curriculum, Disabilities, Financing