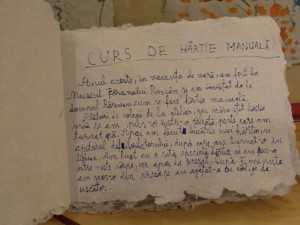

BUCHAREST, Romania | On the first floor of the Romanian Peasant Museum in Bucharest, in the recently opened Cărtureşti library, lies the “Paper Book.” The book is small, with irregular edges, and its pages appear to be composed of remnants of blotting paper, grass, leaves and flowers. Here and there, one can see indistinct printed words. The title of the book is written in the careful, round letters of a child’s handwriting.

The book was made by the students of a paper-making workshop held in July by Răzvan Supuran, a local paper artist who collaborates with the museum. Supuran teaches children how to recycle discarded paper and transform it into something new. It is a simple process, he says, but a very important one because it changes the children’s understanding of paper: “They no longer see it as something you use and then throw away. On the contrary, now they know that a tree is involved, that nature deserves to be respected,” Supuran says.

The children also tell their parents about the importance of recycling paper, thereby transmitting the message to the older generation. The curiosity of some of the parents led them to attend the workshop, themselves, and see how it works with their own eyes.

There are several different ways to make paper, and Supuran likes to experiment with traditional methods. The simplest way, the one he teaches to his students, is to tear up used pieces of paper into small pieces, dip them thoroughly in water, and blend everything with a mixer. The resulting paste looks like wet padding. The paste is then transmitted to a large tub and the children mix in petals and leaves – the latter are not strictly necessary, but add a nice finishing touch. Then every child takes a small sieve, drops a scoop of the paper mixture onto it, and watches as the cellulose fibers arrange themselves as if by magic in the form of a film.

Răzvan Supuran is a graduate of philosophy who worked as a journalist for several years before he decided to devote himself to paper-making. He learned the basic tricks of the trade ten years ago, from Laszlo Matyas, an artist living in Cluj. Supuran worked in Matyas’ shop for three months and mastered the basic techniques, but is now inventing paper on his own out of used paper, industrial cellulose and cellulose he extracts from withered plants, bark and hay.

Supuran says he sets his own challenges. His newest is to perfect the production of “volume paper”, which needs in order to create a piece he started working on some time ago: a paper statue.

“I’m no artist, I’m just a paper maker,” Supuran argues. He says he prefers this term because it shows that what he does is simple, that there is no need to search for complicated words and actions to describe it.

“This is not a business, although I manage to make a living out of it… at least enough to get by,” he explains. His greatest concern is the preservation of the paper making craft. This is why he began teaching it to children – like a master to an apprentice.

The summer workshop gave Supuran the opportunity to grow as a teacher, he says. He is still surprised by the positive feedback of the 20 children, aged 7 to 15, who took his course. When he meets their parents on the street, they stop and ask him when the new course will start because their children want to come back.

One of Supuran’s greatest joys is that he sparked young people’s interest in the age-old craft, particularly those who were initially skeptical. He recalls a 14 year-old boy who protested on the first day of the course, saying that he was only there because he had been forced to come by his mother and was not interested in participating. Supuran let him simply observe during the first class and, to his surprise, the next day the reluctant boy returned by choice.

“The Paper Book” also contains the personal stories of the children who participated in the workshop. When the book was finished, Supuran told them to write down anything they wanted on the blank pages. Most of the children talked about their experiences of the course, as if confessing into a diary. Mara, aged eleven, wrote about the museum and the courses she attended, mentioning that she was “passionate” about the papermaking workshop and giving a detailed account of the techniques she learned.

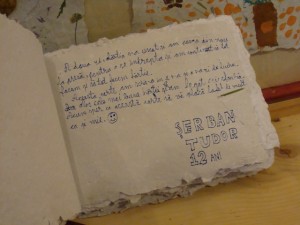

Twelve year-old Tudor wrote that they “continued and continued to make paper” and concluded with: “We wrote this book on the 4th and 5th day. We chose the best paper sheets and we bound them together with a string. Now I hope you will like this book as much as I do.” Then he drew a happy face, and signed his name and age. Thus the “Paper Book” was born.

This article was produced as an assignment for the “Improving Coverage of Education Issues” online distance learning course organized by TOL and developed in cooperation with the Guardian Foundation and the BBC World Trust, enabled by the generous support of the Open Society Institute Education Support Program.

Tags: Environment, Students