ULYANOVSK, Russia | Teaching history in Russia is, in the best of circumstances, a delicate matter. In a single class, teachers can find the children and grandchildren of those who established Soviet power and those who were repressed by it. Sensitivities inevitably run high.

ULYANOVSK, Russia | Teaching history in Russia is, in the best of circumstances, a delicate matter. In a single class, teachers can find the children and grandchildren of those who established Soviet power and those who were repressed by it. Sensitivities inevitably run high.

Such problems go back decades, helping to ensure that, since the beginning of the era of perestroika and glasnost in 1985, the history Russian pupils are taught in school has remained a recurrent theme. In the months before the celebration of Russia’s most important holiday, Victory Day, that question increasingly been narrowed – to what history of the Great Patriotic War Russian children are taught. That too is a deeply delicate matter. Aleksandr Litvinov, a teacher of history from Labinsk in Krasnodar region, recounted in the teachers’ newspaper Uchitelskaya Gazeta in 2004 how a pupil of his once went home after a history lesson and turned to his grandfather: “You said you had won, but in fact Stalin used you as cannon fodder.”

Indisputable Facts and Blank Spots

The only thing that everyone seems to agree on is that teaching of Russia’s war experience is inadequate. Vasily Konevsky, a Hero of the Soviet Union, recently lamented on TV Tsentr that modern-day pupils do not even know the star of a Hero. TV Tsentr itself claimed that “the farther we are from the war, the more we talk about it … the less we know about it.” Some say too little new light is being shed on the period; others worry about the scale of the reassessment.

President Vladimir Putin was, then, just when of many critical voices when, in the run-up to this year’s 60th anniversary of the German surrender, he called for “objective” histories of the war. “They should inform our citizens about the indisputable truth of the events of those years,” the president told the French newspaper Le Figaro.

Some things do indeed seem to be undisputed by historians. Every textbook stresses the role the Soviet people played in that war, and reel off stunning facts: adding that the Nazis lost more than 73 percent of their soldiers on the Soviet-German front, up to 75 percent of their tanks and artillery there, more than 75 percent of their air force.

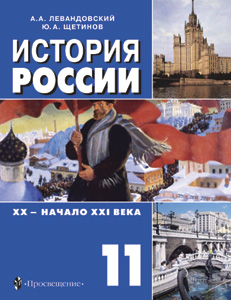

They also emphasize the great price the Soviet people paid: 1,710 Soviet cities and towns were destroyed during the war, Andrei Levandovsky and Yury Shchetinov write in their Russian history textbook for 11th-grade students. Over 70,000 villages were torched. Some 27 million people were killed.

Russian schoolchildren are also taught that it was the contribution of Soviet soldiers that proved decisive in World War II. After all, eight in every 10 of Hitler’s slain soldiers were killed on the eastern front. “The Nazi war machine was broken on a battlefield from the Barents Sea to the Caucasus. Here it was that the main Nazi forces, here it was that the fascists suffered their major losses,” President Putin said during the celebration period. He could have been echoing school textbooks and his interpretation, that “the world has never known such heroism,” is the conclusion that many schoolchildren take away from their classes.

Many young Russians also leave school with the feeling that the Soviet Union was deliberately left to bear the brunt of the war, since their textbooks write that the British and U.S. leaders opened “the second front” in the west only when they understood that the Soviet Union was winning the war against the Nazis.

Those conclusions about the war have been largely undisputed since the war itself. In some ways, they have become evenly more deeply etched, since each Soviet leader has revised the number of war dead and with each revision Soviet sufferings appeared worse. In Stalin’s era, teachers claimed that just under seven million people died. Under Khrushchev, the figure rose to 20 million. Under Gorbachev, it climbed to 27 million, the number now commonly cited and used in textbooks.

Since Stalin died in 1953, the blank spots of Soviet history have also gradually been filled in. But many remain and the Great Patriotic War was always particularly full of blank spots.

What emerges from the textbooks published since Mikhail Gorbachev introduced his policy of openness, glasnost, in the 1980s is that the unprecedented loss of human life on the Soviet front was not just the result of the Nazis’ effort to slaughter Slavs and destroy the Soviet state, but also because of the Soviet leadership’s disregard for casualties and because of Stalin’s policies.

This point is particularly underlined in Levandovsky’s and Shchetinov’s textbook. Here, children learn of Stalin’s repressions and how they weakened the Red Army before the war, how in the purges of 1937-1938, 579 of the 733 most senior commanders (from a brigade chief to a marshal) were killed by Stalin.

Here, as well as in the history textbook for 9th grade by Valery Ostrovsky, they learn about the expulsion of whole nations from the North Caucasus to Central Asia because of their alleged collaboration with the Germans.

Both approved textbooks tell pupils about the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed in 1939, which divided Europe into spheres of influence. In Levandovsky and Shchetinov, they read about Stalin’s attempts to “establish socialism throughout Europe” after the war, though, at the same time, they hear that the Allies wanted Hitler to attack the Soviet Union – or, as the authors put it, about “the secret diplomacy of the Western democracies, who tried to channel Hitler’s war machine to the East.”

But in the debate about Stalin’s interest in creating spheres of influence and his post-war establishment, there remains a blank spot that was put under the spotlight in the months ahead of the anniversary: the incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union after the war. Other complicated problems are also passed over. And while textbooks may write that the Soviet leadership squandered many lives, they say nothing about the many thousands of Russian soldiers killed by their own commanders for allegedly deserting and about the many former Soviet prisoners of war who were treated as traitors and then sent to Stalin’s camps.

Revising the Textbooks

The criticisms of these textbooks are extensive. Some say that the war period is covered too fleetingly, so that schoolchildren struggle to remember even one episode from the war. And some teachers believe that the language of the textbooks is complicated, dry and lacks a human dimension (a failing partially compensated for by the schools themselves, who often invite veterans in to talk about their experiences).

But the main criticisms are about the interpretations of the war. Some teachers argue that too little is said about Stalin’s crimes and the mistakes he made during World War II. Others worry that, in filling in the blank spots, modern history textbooks paint everything in the Soviet Union black and compare Stalin’s regime to that of Adolf Hitler. The sociologist Aleksandr Tarasov believes that the authors of history textbooks have taken upon themselves the task of spreading the “propaganda of anti-communism” rather than teaching history.

In 2003, some World War II veterans decided that this had gone too far, and called on Putin to prevent the “distortion of history” in some textbooks. “I share the feelings and opinions of the veterans of the Great Patriotic War,” Putin responded. His then-education minister, Vladimir Filippov, said there should be no space for “pseudo-liberalism” in history books, rhetoric that echoed the veterans’.

For a long period, the state played little attention to history teaching. Prior to 1997, large numbers of textbooks were produced without state control, leaving schools themselves to choose the books they wanted. It was a period that Tarasov describes as “anarchy.” In 1997, courses began to be stamped and certified by the Education Ministry and, from 2001 onwards, the state’s interest in history teaching grew. However, it was only in 2004 that it made a direct impact, by deciding to approve and pay for just three textbooks on each subject.

Despite the tighter certification process introduced in 2004, some in the Kremlin are openly expressing their unhappiness about how the war is presented in textbooks. Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov made just one of a number of criticisms when, on 7 May, he declared that the history texts “contain a lot of nonsense.” The state should publish new history textbooks, he suggested.

Ivanov stressed that he was not calling to just one textbook, but added that “playing with historical facts is not possible.” He did not specify, however, what facts have been distorted and which authors had done so.

One book that failed to gain state support was Igor Dolutsky’s Russian History: The 20th Century for 10th and 11th grades. It is no longer published, even as an alternative source of information. Dolutsky’s textbook does not fill in some of the blank spots in other textbooks. He also indicated that an undemocratic system was crucial to the Soviet Union’s victory. “No democracy could have endured our war, because it could not have paid our price,” Dolutsky wrote. Nonetheless, Dolutsky’s book was clearly highly critical of the system created by Stalin, stressing Stalin’s mistakes and crimes more than awakening feelings of patriotism among schoolchildren. He also wrote about the incorporation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union, and challenges the official view that the Allies tried to encourage Hitler to attack the Soviet Union.

If Ivanov’s criticisms are acted on, it seems likely that officially approved textbooks will steer well clear of the types of criticisms made by Dolutsky and blank spots will remain blank. Putin himself has said in the past that textbooks should “cultivate a sense of pride among the young in their history, in their country.” The question is whether that interest in nurturing national pride will allow much attention to be paid to the negative aspects of some of Stalin’s war policies.

At the same time, the number of official textbooks may be reduced. In 2004, Education Minister Andrei Fursenko suggested one or two might be enough. In recent months, there has also been speculation that textbooks could be distributed free of charge to pupils, but that, some believe, might result in the government reducing the number of official textbooks to just one.

There may also be more classroom time devoted to history. Some commentators are scathing about the lack of space devoted to this key period of Soviet history. “In three lessons nothing can be taught other than the fact that the war took place,” Tarasov told the website of the Social Democratic Party (founded by former Soviet leader Gorbachev) on 5 May. “As a result, such school essays appear: ‘They had Napoleon, and we had Stalin. Stalin was stronger and we won,’ ” Tarasov said.

Four modules in the history curriculum are devoted to the war, and the war fills nearly 40 pages in Levandovsky’s and Shchetinov’s textbook. (Dolutsky’s textbook devoted 60 pages to the period.)

Calls for more focus on history have also been aired on state-controlled television. TV Tsentr pointed out that the government had spent 530 million rubles ($19 million) just on the Victory Day celebrations in Moscow, allocated some 1 billion rubles (roughly $36 million) for extra social benefits for veterans – but “not a single kopeck into turning children into patriots.”

“The Ministry of Education virtually has legitimized the lack of memory,” it concluded.

So far, the Kremlin has not indicated whether history teaching will receive extra money or whether more classroom time should be devoted to the war, but Ivanov, in his comments to veterans from the Moscow region, clearly lamented pupils’ gaps in knowledge. “Many schoolchildren do not know who won in this or that battle,” he asserted.

It seems possible that more emphasis on Russian and Soviet history may be in prospect, but there seems little chance that aspects of the war not covered in the past 15 years will be addressed now. The Russian writer Daniil Granin recently said that the full history of the Great Patriotic War has yet to be written. That full, rounded history may still be some time away.

Tags: Conflict