TBILISI | In 2004, some 5,200 Georgian children were living in Soviet-era institutions for underprivileged and disabled minors. Today, there are just 100, seemingly a sign that Georgia’s ambitious Child Action Plan – which aimed to reintegrate socially vulnerable kids into their biological families or, failing that, get them into foster care or alternative types of support – has worked. By contrast, neighboring Armenia, with a somewhat smaller population, still houses 4,900 kids, most of whom have families, at its aging children’s homes.

TBILISI | In 2004, some 5,200 Georgian children were living in Soviet-era institutions for underprivileged and disabled minors. Today, there are just 100, seemingly a sign that Georgia’s ambitious Child Action Plan – which aimed to reintegrate socially vulnerable kids into their biological families or, failing that, get them into foster care or alternative types of support – has worked. By contrast, neighboring Armenia, with a somewhat smaller population, still houses 4,900 kids, most of whom have families, at its aging children’s homes.

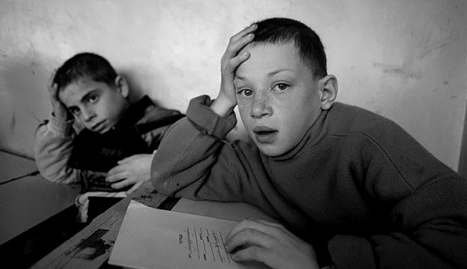

But there is a flip side to Georgia’s seeming success: unlike in Armenia, street children – minors who spend most of their time roaming the cities, in many cases sleeping rough – have become increasingly visible in the capital of Tbilisi and other urban centers like Kutaisi and Batumi.

“The process of de-institutionalization started in 2000 and out of 42 institutions, only five are left today,” said Andro Dadiani, Georgia director for international children’s rights groupEveryChild. “De-institutionalization has obviously contributed to the problem [of street children], and especially ill-prepared reintegration.

“We have some anecdotal examples of cases when the same children taken out of institutions were later seen begging in the streets, and the main reason was that some social workers were not doing their job well, especially in terms of monitoring,” Dadiani added. “As a result, the issue of street children has been totally neglected over the past few years.”

According to UNICEF, there were approximately 1,500 children living or working on the streets of Georgia’s biggest cities in 2008. Precise figures are hard to come by because many of these children lack proper documentation, such as birth certificates or passports, which also means they cannot attend school. In recent years their numbers have probably increased, swelled by young children believed to be Roma, Dom, or Kurds from Azerbaijan. Aid groups such as World Vision and the local Child and Environment attribute the influx to tight restrictions on begging in Azerbaijan.

Many Georgians dismiss the problem as only afflicting minority groups. International organizations are trying to dispel that notion, but the issue remains largely ignored here. That could change with a new two-year, 850,000 euro ($1.1 million) effort funded by the European Union and UNICEF, called Reaching Vulnerable Children in Georgia. Rolling out in Tbilisi and set to expand next year to Batumi or Kutaisi, the project will use mobile teams of social workers, psychologists, and educators and new transitional and day-care centers to identify some 700 street kids and get them into existing child-protection and social-service systems.

“Children who are on the streets cannot access education [or] proper health care, are often not registered, and can become subject to various forms of violence,” said Sascha Graumann, UNICEF’s representative in Georgia, at the launch of the program on 27 February. “This means that they have fewer chances to become active and well-educated citizens that can make a contribution to the development of the country. Addressing this issue requires interventions to restore their human rights.”

Some journalists at the launch were skeptical as to what will happen after the project ends, but Maya Kurtsikidze, UNICEF Georgia’s spokeswoman, told TOL that the creation of a “self-sustainable state mechanism” is envisaged, with the Finance Ministry among potential partners who will “ensure financial sustainability” for the effort.

Onnik Krikorian is a journalist and photographer in the South Caucasus and former Caucasus editor for Global Voices Online.