In the hundreds of articles TOL has published on education in the post-communist world in the past decade, low teacher salaries are blamed for innumerable ills, from teacher shortages to corruption in education to slipping teaching standards. So we set out to discover what teachers really earn across our region, and how those salaries compare with their counterparts elsewhere and with living standards in their own countries. There was no simple way to do this, as teachers are paid via different methods in different countries (for instance, in many former Soviet states they are paid according to their workload, whereas elsewhere they are paid by the week), and as various organizations measure pay differently.

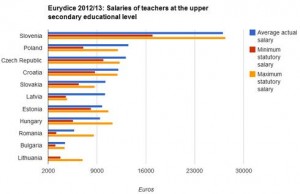

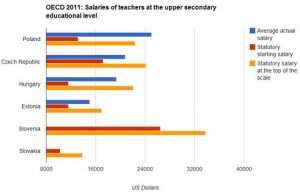

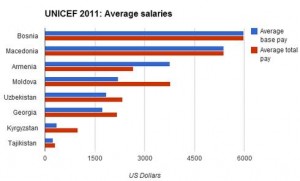

We consulted three publications covering a total of 19 countries: Teachers’ and School Heads’ Salaries and Allowances in Europe 2012/13 by Eurydice, an EU education research program; the OECD’s Education at a Glance 2013; and a 2011 UNICEF study on teachers’ recruitment, development, and salaries in Central and Eastern Europe and much of the post-Soviet world.

We found a huge variation in teachers’ salaries regionally. The 27,000 euros ($37,000) that teachers at Slovenia’s upper secondary school (ages 15 and up) averaged in 2012 put them atop two rankings. Another survey, from 2011, found the average teacher’s pay in Tajikistan to be less than 1 percent of that.

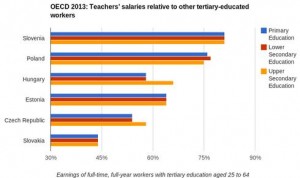

Low salaries also provide little motivation for young people to enter teaching in Georgia, Uzbekistan, Moldova, and Armenia. OECD research in Hungary, Estonia, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia found that professionals in other fields with similar educations and levels of work experience earn significantly more than teachers do.

Slovenian Teachers on Top

According to Eurydice research, Slovenian high school teachers’ average actual salary (the statutory pay rate plus extras such as reimbursements for continuing education, bonuses for working in remote areas, or overtime or seniority pay) is more than the salaries of Polish and Czech teachers – numbers 2 and 3 in the rankings – combined.

Bringing up the rear in the Eurydice sample, Bulgarian teachers’ average actual salary is only about 4,400 euros, or 16 percent of what Slovenian teachers make.

Notably, Latvian teachers have some of the lowest statutory salaries in the survey, ranging from 4,567 to 4,757 euros, but they take home nearly double those figures when allowances are taken into account, putting them in the middle of the earnings pack.

Findings from the OECD report, which uses dollars instead of euros and did not provide actual salaries in every case, echo some of those in the Eurydice research.

Absent data on Slovenian teachers’ actual salary, Polish teachers in secondary education sit atop the chart, bringing home an average of $25,000, thanks largely to salary-boosting extras. Estonian teachers bring up the rear for actual salaries, among countries where that information was available. They make an average of $15,030 in upper secondary, or high, schools.

A UNICEF study in 2011 looked at teachers’ pay across all grade levels in countries that are poorer than those surveyed by the OSCE and Eurydice. Researchers focused on six countries but included two more in the salary chart – Georgia and Tajikistan – because data from those countries were available from another study that used similar methodology. It should be noted that the salaries for the original six countries apply only to teachers with a higher education degree, although that distinction probably makes little difference, as wages for teachers in Tajikistan start from such a minuscule base that even with university diplomas, they would not likely catch up with their counterparts elsewhere.

At the top of this chart sit teachers in Bosnia, with annual salaries at $5,976, compared with an astonishing $312 total average pay for teachers in Tajikistan. Armenian teachers’ actual salaries are lower than their base pay because many do not teach a full load.

It Pays Not To Teach

Clearly, teachers in some countries earn a pittance. But to see how that affected their livelihood, given that the standard of living is also quite low in some of these countries, Eurydice matched data on gross statutory salaries in primary, secondary, and upper secondary education (ISCED 1, 2 and 3), with the gross domestic product per capita (denoted as 1 on the chart above).

In none of the countries surveyed did teachers’ entry-level wages (minimum gross statutory salary) reach GDP per capita, although Slovenian teachers came close. New teachers in Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and Slovakia fared worst in this measure.

Later in a teacher’s career, things get rosier for those in secondary education, but primary school teachers still make less than the average GDP per capita in most of the countries surveyed.

Although not included in the Eurydice research, the shockingly low statutory salaries for teachers in Kyrgyzstan ($360) and Tajikistan ($240) in 2011 amounted to about 32 percent and 29 percent, respectively, of those countries’ GDP per capita.

When compared with those of other workers with the same level of education, teachers’ pay in countries in the OECD research provides more evidence of why many graduates choose not to enter the profession. In none of the countries do teachers’ average statutory salaries reach those of similarly educated workers. The situation is especially demoralizing for teachers in Slovakia, who make on average less than 45 percent of what people of matching educational achievement earn in other fields.

Teachers’ salaries in all the countries in the UNICEF research sit well below the national average. In Georgia, teachers’ salaries stagnated from 2005 to 2009, barely rising above subsistence level, unlike those of police officers, which went from around 450 percent of the subsistence level in 2005 to more than 900 percent in 2009, in an effort to stem corruption.

At a Glance

The list below shows all the countries in the publications consulted, ranked by the actual salary where available. The studies’ differing time periods and methodologies make true comparisons impossible. Nevertheless, a clear picture emerges of an undervalued profession, which in turn helps account for alarming reports of unqualified teachers in Georgia and Kyrgyzstan; understaffed rural schools in Moldova; corruption in Georgia, Uzbekistan, and Armenia; and widespread teacher discontent in Central Europe, to name only a few places. And the average base monthly salary of 15 to 20 euros in Tajikistan speaks for itself.

How do these numbers affect student performance? A 2011 study of 27 countries found a link between rising teacher salaries and rising test scores.

Low pay “is responsible for lower-ability people recruited to the profession and worse educational achievement outcomes for pupils,” Peter Dolton, an economist with the Royal Holloway College in London and one of the study’s co-authors, wrote in an email.

The problem persists in post-communist countries because, among other reasons, teachers’ unions are weak or public servants in the region were historically poorly paid, a trend more marked now “when the private sector is expanding and paying better,” Dolton said. He cautioned, though, that salaries might not tell the whole story, noting that some teachers “benefit from: lower retirement ages, higher pensions, better health care provision, subsidized housing, longer holidays, etc.”

Finally, he wrote, “The population and voters accord teaching low status and hence such jobs are not those that young people want to go into.”

As for Slovenian teachers, who enjoy relatively high salaries in a highly rated educational system, it remains to be seen how they will weather the country’s austerity measures, which include cuts to their pay.

Karlo Marinovic is a TOL editorial intern. Home page photo by Bahai.us/flickr.

Tags: Corruption, Research & quality, Teachers, Teaching