Education can’t be separated from politics. The political system of a society will directly and indirectly influence the education system and this will also motivate challenge and opposition to both.

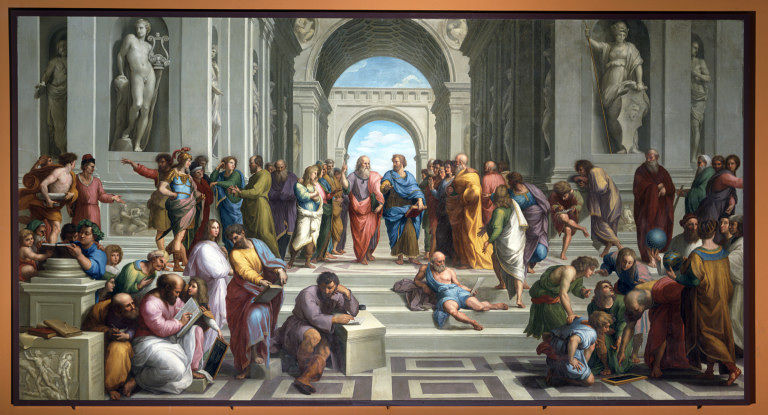

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons under CC Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Image by Adonia.

Well, my first thought is that education must have something to do with one person or group wanting to have control or power over another. How could a system or process such as education come about for any other reason? Or perhaps it was the early process of findings things out so as to aid development and progress and was passed on to others as co-operation to help them do the same? Or a combination of these two. Or perhaps education developed as a process and system for wholly other reasons.

However it began, it has become an established system, a comprehensive process and a compulsory activity. All societies everywhere value education: it is a universal good thing. Our children and young people must be educated. Why? How did it become such a universal necessity? The idea that education is a social good is a difficult one to challenge.

Education can’t be separated from politics. The political system of a society will directly and indirectly influence the education system and this will also motivate challenge and opposition to both. That education cannot be neutral is an axiom. But it can’t be seen to be wholly ideological either, at least not in parliamentary democracies. Balance, that most arbitrary of concepts, is at the heart of most educational systems. A balanced argument, one that takes into account both sides of the story is one of the highest valued of concepts, particularly in western capitalist democracies.

And balance is taught in our schools and our universities. Beware the totalitarian perspective. And the alternative taught is that we must see both sides of the argument: religious and atheist; competition and co-operation; black and white; right and left; Catholic and Protestant; Christian and Muslim; East and West; carnivore and vegetarian etc. etc. Binary divides then seem to dominate this ‘balanced’ view of the world. Both sides are deemed to be valid, both are worthy of consideration and deliberation. In fact it is essential to take into account both perspectives.

Life, in fact, actually might be more nuanced, more complex, more contingent, more fluid than this and not merely made up of a set of binary perspectives. If this is the case, then what are the implications for a ‘balanced education’?

It could be a myth, a smokescreen, a distraction so that capitalism can continue with its endless profit-seeking. It could be an over-simple notion of attempting to present more than one perspective. It could be a mistaken and misguided attempt to be fair, to be even handed, to give both sides a fair crack of the whip.

How about ideas, thoughts, feelings and notions that don’t fit into either side? And just in case you were wondering, these ideas are not in the ‘centre’ either. They are not a compromise between the two. They are not pleasing everyone or even some people some of the time. They are ideas that just are, not categorisable, not located on a spectrum. Maybe, binary divides, categories, spectra, continua, labels and compartments are part of the problem? They actually contain so-called problems which then remain forever unaddressed, unsolved and constantly replayed. You only need to be alive for around 20 years in the West before you to begin to notice a recycling of these social and educational problems.

Should schools be doing more to address bullying? What can we do about teenage pregnancy? Is immigration too high? How do we get taxation levels right? Can we afford an NHS but can we do without it? What can governments do about economic inequalities? Is global warming inevitable? Is private education better than state? Should public spending be curbed? Are A levels marked too generously?

If you live for a lot longer than 20 years, you have seen these and many other ‘problems’ recycled over and over again by the media and the state. It gets very tedious and many of us give up listening and thinking about them. Cynicism is the inevitable result.

These social problems or questions are always, or almost always, situated within a binary perspective. Left(ish) and right(ish) is a common one in western democracies. Others are free market and state intervention and competition and co-operation. Binary divides are often presented as opposing perspectives and equally often a balanced view implies that they must be combined, a compromise must be sought: a mixed economy; a progressive taxation system, a low inflation, high growth economy. Binary divides require arbitration, a bringing together and mixing of the two.

Are our lives actually like this? As a construction, they are. Could ideas that can’t be categorised in the way that is described here upset the consensus? Can they challenge the idea of balance based upon binary divides? Perhaps.

This categorisation and division of ideas into convenient binaries forms very palatable discourses, for the paper, broadcast and electronic media and for politicians, which then become something of a universal common sense. This process is characteristic of the dominant discourses of the western democracies. We are fed a diet of ideas that seem immediately palatable, no matter how unpleasant tasting they are to some of us. Ideas based upon so-called common-sense seem to be unchallengeable. They reserve a place in our hearts and our minds. Terrorism is evil, teenage parents are a social problem and obesity is the responsibility of the individual

Media, in its many and varied contemporary forms, employ categories, invariably based upon binary perspectives, that provide us with the news in ways that we find immediately recognisable and digestible for being such. Again for some of us, the result is boredom and cynicism.

It seems all too easy for ideas to be compartmentalized in this way. Philosophical discourse often eludes this treatment because of its complexities. It is sometimes characterized as obscure, self-referential and elitist and some of these criticisms seem justified. The gulf in understanding between popular and philosophical discourse is enormous. Yet philosophies also often contain challenges and threats to the dominance of popular common-sense. They provide us with a source of ideas that are, at least potentially, not susceptible to the manipulation of the media and politicians. Hope seems to be present here in the form of different approaches to knowledge, language and discourses.

Initially post-structuralist thought, and then the various and myriad strands of intellectual development that have emerged from it and in response to it, invite us to think of the world, social, environmental and technological, anew. Ideas that emerge may avoid the crunching treatment often applied by the powers that be within the media and politics. Hope presents some possibilities.

This post was written by Paul Allender and was originally posted in openDemocracy. It is republished under a Creative Commons license.

Tags: Civil society, Development