To get a handle on the extent of reforms introduced in England by Michael Gove, the former Minister of Education, we asked David Eddy-Spicer to share with IEN some of what he has observed while he has been a Senior Lecturer at the University of London’s Institute of Education. Eddy-Spicer returned to the US recently to take a position as Associate Professor at the Curry School of Education, University of Virginia.

This summer, I left one academic post for another, returning to America after six years in England. The person who had the greatest influence on my experience of education policy and schooling over that time also traded in one post for another this summer. In a Cabinet reshuffle, the former UK Minister of Education, Michael Gove, stepped down after four years to take up duties as Chief Whip. The post of Chief Whip was made most famous fairly recently in the original British House of Cards, a TV series that went viral when Americanized with Kevin Spacey in the leading role. Sentiment about Gove and his legacy are about as heated and mixed as the sentiment the protagonist of House of Cards managed to stir. Gove had few friends among my academic colleagues in the education establishment, whom he referred to as ‘The Blob’, a term popularized by a former Chief Inspector of Schools in England. The school leaders I was fortunate to work with were for the most part perplexed, confused and anxious about the changes that Gove introduced. In an Ipsos MORI “State of Education” survey carried out this spring, three-quarters of school leaders expressed dissatisfaction with the current government’s performance on education, with almost half (46%) saying they were very dissatisfied and only 8% saying they were satisfied. The reaction among teachers has been even more pitched against recent government policies, especially changes to the curriculum and the mandatory adoption of performance-related pay.

As unpopular as Gove has proven to be among academics and educators, he and his Department were extraordinarily effective at initiating widespread change in the structure of schooling in England. I was astounded at the pace and extent of change the Department for Education managed to orchestrate since he assumed his duties with the election of the Coalition Government in 2010. There is no doubt that the changes he oversaw have radically altered the landscape of English education in a span and to a degree that is unimaginable in a country like the US where the power resides at the district and state levels.

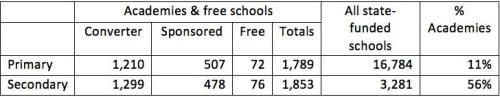

The policies that were of greatest concern to school leaders in the Ipsos MORI poll had to do with the rapidity with which and the ways in which school autonomy has been promoted. The recalibration of the relationship between the state and schools began several decades ago; however the current government has greatly accelerated the push for schools and school groups to become independent of local government control. The Department for Education has encouraged schools graded as ‘outstanding’ and ‘good’ to convert to state-funded independent schools, known as ‘academies’ in England, similar to charter schools in the US. The promotion of academies occurred through a relatively modest financial incentive as well as the promise of greater operational freedoms, including hiring and firing of staff, the school timetable and even, to some extent, control of the curriculum. But it also entailed diverting funds from the middle tier, the local educational authorities, so that good schools, “converter academies,” would have direct access to state funds in exchange for their entering into a direct relationship with the Ministry. At the other end of the educational quality spectrum the lowest performing schools were required to become “sponsored academies,” that is schools under the sponsorship of an outstanding school or, more frequently, a non-profit ‘academy chain’ or educational management organization. (For-profit academy chains are not allowed under current law.) Government policy also gave groups of parents, educators or non-profits, including religious organizations, the possibility of creating new schools, “free schools,” modeled after a similar initiative in Sweden. The net effect of these changes resulted in the development of a significant number of academies, particularly at the secondary level.

Numbers and Percentage of Academies among All State-funded Schools in England

Data drawn from UK Government National Statistics, Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2014, Tables 2a, 2b. See also, UK Department for Education, Academies annual report, academic year: 2012 to 2013.

It is too early to tell what the impact on student outcomes, school performance and system dynamics will be over the long haul. I have been part of a group of researchers funded by the British Educational Leadership, Management and Administration Society to look into the effects of these structural reforms. Initial results so far, published in a special issue of the journal Educational Management, Administration and Leadership raise concerns about equity, access, and control of the educational system now in a new era in which local government has a far more constrained role in education.

With national elections looming in the spring of 2015, it’s clear that the current coalition won’t hold, but it’s not clear what will arrive in its place. Will Michael Gove be remembered for his hubris, akin to the House of Cards protagonist, or will he be remembered for spawning a self-improving school system? Some aspects of change appear to be irreversible at this point, especially changes to local government. One thing is certain–structural reform in England brings into sharp focus a host of questions about state-school relations, the professional responsibilities of school leaders and educators, and the role of non-state institutional actors in what has been a public service. How to learn from these lessons is the good work that my colleagues in ‘The Blob’ are undertaking as we speak.

This post was written by David Eddy-Spicer and was originally posted on internationalednews.com. Home page photo by Anna Armstrong/ Flickr Commons.

Tags: Conflict, Financing, Policy, Reform, Research & quality