TASHKENT, Uzbekistan | A planned switch from a version of the Cyrillic script introduced for the Uzbek language under Joseph Stalin nearly 70 years ago to the Latin alphabet is slated to be completed in Uzbekistan within a few years, but few believe it will happen.

Many, in fact, are convinced that the country of 28 million, where nearly three-quarters of the population speaks Uzbek, will return to Cyrillic.

Uzbekistan passed a law replacing the Cyrillic alphabet with a Latin script modified for Uzbek, a Turkic language, in 1993, and the transition should have been completed by 2000. The need to communicate with the outside world using a more universally understood alphabet (similar to that used in Turkey) was cited by the government as the main reason for the switch. At the same time the move signaled Tashkent’s desire to break away from its dependence on Russia and to shift to the West. Some prominent Uzbeks even expressed the hope that English, study of which became common in the early 1990s, would replace Russian as the language of international communication in Uzbekistan.

But the full switch has been postponed twice, to 2005 and then to 2010. Rumors say the deadline may be pushed back yet again.

Let it Drop

A prominent political scientist from Tashkent who is close to the government said on condition of anonymity, “More than likely, the law will simply be allowed to drop” because it is very difficult “to acknowledge mistakes.” The country doesn’t have the resources to complete such a transition, and political, business, and intellectual leaders are not ready for it, he said.

Per person gross domestic product in Uzbekistan last year was around $2,000, less than a quarter of that in neighboring Kazakhstan and less than one-sixth of that in Russia.

Information on educational financing in the country is closely guarded, and therefore estimates made by outsiders are sketchy and should be used with caution. Still, a 2002 report by the Open Society Institute’s Education Support Program stated, “The percentage of the GDP spent on education dropped… by a third in Uzbekistan” in the 1999-2000 school year.

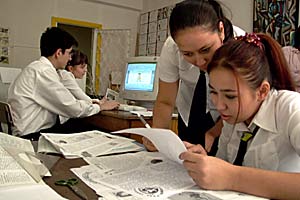

The Latin alphabet began to be used in schools in 1996 and since then an estimated 5 million students have learned it. But the government has not had the money to furnish them with all the necessary textbooks and materials in the Latin script.

“Mostly affected are Uzbek students. … Presently, they have only the essential textbooks in the Latin alphabet, while the remaining learning materials (references, manuals, etc.) are available in Cyrillic only,” the OSI report stated.

In addition to schools, the Latin alphabet is used on street signs and a few other places. Business correspondence, media, and government documents must be issued in the Latin script by the 2010 deadline, but are mostly still written in Cyrillic, as are most types of literature.

A recent scan of newsstands in Tashkent turned up just a few children’s books printed in the Latin script. Everything else was in Cyrillic.

“I have no newspapers or magazines available in the Latin alphabet. Adults wouldn’t buy such media because they can’t read in the Uzbek language based on the Latin alphabet,” one vendor said.

Linguistic Questions

Contrary to the version of the Cyrillic script consisting of 35 characters, the new official Latin-based alphabet includes 26 letters, three combinations of letters, and the apostrophe, totaling 30 characters. The combinations of letters – sh, ch and ng – designate sounds similar to those in the English language.

When the country’s relations with the United States and other Western states soured as a result of the brutal suppression of an uprising in the town of Andijan in May 2005, where scores were killed by troops firing on demonstrators, the new system’s similarity to the English alphabet and language attracted criticism from official linguists.

Shavkat Rahmatullayev of the National University of Uzbekistan maintains that the switch to the Latin script was an appropriate step but acknowledges some deficiencies. “[Unfortunately,] some sounds are conveyed with two letters, which was adopted under the influence of specialists in the English language,” he said. According to him, another defect is that one letter can designate different sounds.

Political scientist Tashpulat Yuldashev is not delighted with the new script, either. “Because of apostrophes, it is difficult to hand-write fast using this version of the Latin alphabet,” he said. “The switch to it has not been prepared thoroughly and, as a result, the nation has not assimilated the alphabet into everyday life. Colossal money was thrown to the winds.”

The Horns of a Dilemma

Experts believe the introduction of the Latin alphabet resulted in a general reduction in the quality of the country’s scientific and cultural works and even its literacy rate. The scientific and cultural legacy accumulated over the previous half a century is dissipating.

“My 11-year-old daughter, who finished the third grade this year, does not know Russian,” Rakhmatjon Kuldashev, a prominent Uzbek poet and journalist, said. “I have taught her to read [Uzbek based on] Cyrillic but she has difficulty understanding this script.” He said about 80 percent of the books he owns are in Russian, with the rest in Cyrillic Uzbek.

Kuldashev believes that every switch from one alphabet to another throws the country 15 to 20 years back because of the huge disruption to education and the country’s intellectual life. Uzbekistan has suffered such switches four times in the last century – from the Arabic script to the Latin alphabet in the 1920s, to Cyrillic a decade later, to a new version of the Latin alphabet in the early 1990s, and to the current version of the Latin script in 1995.

The recent transition has resulted in a conflict between adults who use Cyrillic and young people who have learned to read and write in the Latin alphabet.

“While my daughter has difficulty reading in Cyrillic and my 9 year-old son can’t read in it at all, it’s hard for me to read Uzbek books in the Latin script,” Kuldashev said. “It’s also difficult for me to read what my children have written.”

It looks as though whatever Tashkent chooses to do it will only worsen the situation.

The continuation of the forced transition to the Latin alphabet will cost the country its scientific and intellectual potential, but Uzbekistan’s possible return to Cyrillic raises another issue: what to do with all those schoolchildren taught in the Latin script?

Tags: Conflict, Minorities